Silent Hunters: The Untold World of Owl Conservation

The ethereal hooting of owls in the night has captivated human imagination for millennia, yet these mysterious birds face unprecedented challenges in our rapidly changing world. From habitat loss to climate change, owl populations across the globe are experiencing significant pressures, prompting innovative conservation strategies and research efforts. While many people recognize owls for their distinctive appearance and nocturnal habits, few understand the intricate ecology and conservation issues surrounding these remarkable predators. As keystone species in their ecosystems, owls provide essential natural pest control and serve as indicators of environmental health. Their future depends on our understanding of their needs and our commitment to preserving the wild spaces they call home.

The Silent Sentinels: Understanding Owl Diversity

Owls represent one of nature’s most specialized and successful evolutionary designs, with approximately 250 species distributed across every continent except Antarctica. These raptors range from the diminutive Elf Owl, weighing barely 40 grams, to the impressive Blakiston’s Fish Owl that can reach nearly 4.5 kilograms. While their distinctive facial discs and forward-facing eyes are universally recognized, each species has adapted to specific ecological niches. The Snowy Owl thrives in Arctic tundra, while the Burrowing Owl makes its home in underground tunnels across grasslands. The specialized anatomy of owls includes asymmetrical ear placements that allow for pinpoint sound location, serrated feather edges for silent flight, and incredibly flexible necks capable of rotating up to 270 degrees. This diversity represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement, yet many species remain poorly studied due to their nocturnal habits and remote habitats. Conservation efforts must account for this variety, as different owl species face unique challenges across their diverse ranges.

Crisis in the Forest: Threats to Owl Populations

The primary threat facing owl populations worldwide is the rapid destruction and fragmentation of their habitats. Old-growth forests, crucial for cavity-nesting species like the Spotted Owl, continue to disappear at alarming rates due to commercial logging, agricultural expansion, and urban development. Even protected areas face degradation from climate change, which alters precipitation patterns and increases wildfire frequency. Rodenticide poisoning presents another significant danger, as owls consuming poisoned prey suffer secondary toxicity effects, resulting in internal bleeding and death. Light pollution disrupts hunting patterns and breeding behaviors, while vehicle collisions claim countless owl lives annually as the birds hunt along roadways. Invasive species compound these challenges, with introduced predators threatening ground-nesting owls and non-native plants altering hunting habitats. In developing regions, some owl species face direct persecution due to cultural superstitions associating them with death or misfortune. The cumulative impact of these threats has resulted in declining populations for numerous species, with at least 20 owl species currently classified as endangered or critically endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Conservation Success Stories: Models for Future Protection

Despite the challenges, targeted conservation efforts have achieved remarkable successes for several owl species. The Northern Spotted Owl became an iconic conservation symbol in the 1990s, leading to protection of millions of acres of old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest through the Northwest Forest Plan. While controversial at the time, this initiative demonstrated how a single species could drive ecosystem-wide protection. In Israel, the Barn Owl Project represents another innovative approach, where farmers install nest boxes to encourage owl residence, providing natural rodent control and reducing pesticide use. Since its inception, the project has expanded throughout the Middle East, building environmental cooperation across political boundaries. In urban environments, cities like Phoenix have pioneered Burrowing Owl relocation programs, successfully moving colonies from development sites to artificial burrow systems in protected areas. Technology has enhanced conservation efforts, with satellite tracking revealing previously unknown migration patterns and habitat needs for species like the Long-eared Owl. Community science initiatives have also proven valuable, with programs like the Global Owl Project engaging thousands of volunteers in monitoring efforts. These success stories provide templates for future conservation work, demonstrating that effective intervention can reverse population declines when properly implemented and supported.

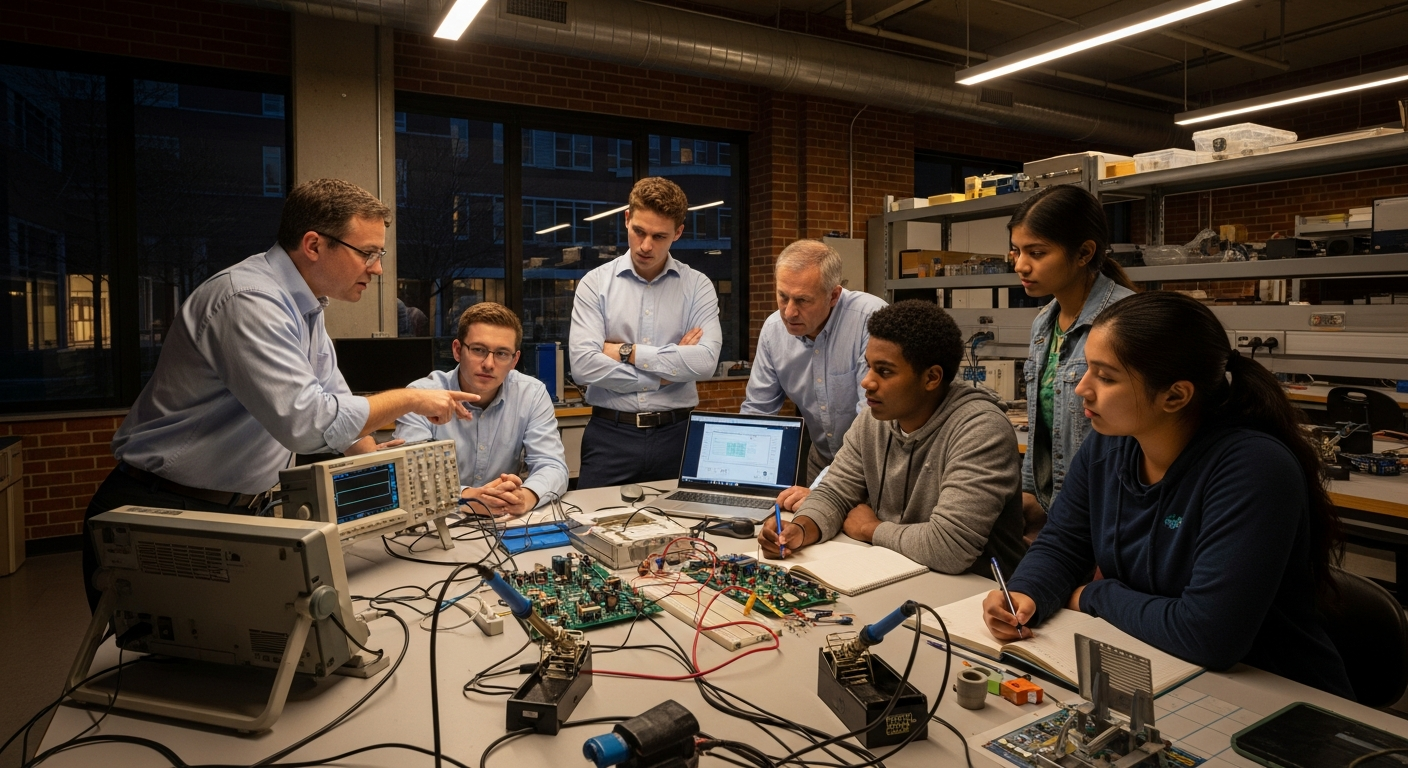

The Science of Owl Conservation: Research Driving Protection

Advanced research methodologies have transformed owl conservation in recent decades, providing crucial data for effective management strategies. Genetic analysis now reveals population connectivity and diversity levels, helping identify at-risk populations before visible declines occur. The genetic distinction between Mexican and California Spotted Owls, for example, has led to tailored conservation approaches for each subspecies. Acoustic monitoring technology enables researchers to survey vast areas for owl presence by recording and analyzing night calls, with artificial intelligence increasingly automating the identification process. These methods have documented previously unknown populations of rare species like the Critically Endangered Forest Owlet in India. Camera trap networks provide insights into nesting behavior and prey selection without human disturbance, while sophisticated habitat modeling combines satellite imagery with field observations to predict suitable areas for conservation focus. Research into owl dietary needs has revealed surprising ecological connections, such as the dependence of some forest owl species on flying squirrels, which themselves require specific forest conditions. Toxicology studies have documented the bioaccumulation of rodenticides and other environmental contaminants in owl tissues, providing evidence for regulatory changes in pesticide use. The price of conservation research has decreased significantly with technological advances, with acoustic monitoring units now available for approximately $200-500, compared to $1,500-2,000 a decade ago, making widespread deployment more feasible for conservation organizations with limited resources.

Community-Based Conservation: Engaging the Public in Owl Protection

The most successful owl conservation initiatives recognize that sustainable protection requires public engagement and support. Educational programs targeting schools have proven particularly effective, with the Raptor Education Foundation’s traveling owl ambassadors reaching over 100,000 students annually across North America. These presentations not only generate enthusiasm for owl conservation but also dispel harmful myths about these birds. Citizen science projects like the Global Owl Acoustic Survey enable amateur naturalists to contribute meaningful data by recording owl calls in their local areas, with participants in over 40 countries. Land trust organizations have increasingly focused on securing critical owl habitat, with innovative financial mechanisms allowing private landowners to receive tax benefits for conservation easements that protect nesting sites. In agricultural regions, certification programs reward farmers who implement owl-friendly practices, such as installing nest boxes and reducing rodenticide use. The economic value of these natural pest controllers is substantial, with a single Barn Owl family consuming approximately 3,000 rodents annually, saving farmers an estimated $300-1,200 in crop damage and chemical controls. Indigenous knowledge has also gained recognition in conservation planning, with traditional ecological understanding of owl behavior and habitat needs informing management strategies in regions from the Arctic to the Amazon. By integrating community involvement with scientific research, conservation efforts become more culturally relevant and economically sustainable, increasing their likelihood of long-term success.

The Future of Owl Conservation: Innovative Approaches

As conservation challenges evolve, innovative strategies are emerging to protect owl populations for future generations. Habitat corridor initiatives seek to reconnect fragmented landscapes, allowing owls to move between isolated forest patches. In urban environments, green infrastructure planning increasingly incorporates owl habitat requirements, with cities like Seattle designing parks and greenways that support urban-adapted species like Barred and Western Screech Owls. Advances in genetic technologies offer potential conservation applications, with scientists exploring strategies to increase genetic diversity in isolated populations through targeted translocations. Climate adaptation planning has become essential for owl conservation, with managers identifying and protecting “climate refugia” areas projected to remain suitable despite changing conditions. International cooperation has strengthened through agreements like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which provides legal protection for owls crossing national boundaries. The economic model of conservation is also evolving, with innovative funding mechanisms like environmental impact bonds that connect conservation outcomes to financial returns. The ecotourism potential of owls remains largely untapped, though responsible owl-watching experiences now generate approximately $3-5 million annually in specialized tourism revenue worldwide. While challenges remain significant, these multifaceted approaches provide hope for owl conservation. By combining traditional protection measures with cutting-edge science and community engagement, we can ensure these magnificent birds continue to fulfill their ecological roles while inspiring wonder in future generations.