Legal Deserts: Access to Justice Crisis in Rural America

The concept of equal justice under law stands as a cornerstone of the American legal system, yet millions of Americans face a troubling reality—they live in what experts call "legal deserts." These vast stretches of rural America have alarmingly few practicing attorneys, creating barriers to justice that urban residents seldom encounter. The disparity has grown steadily worse over the past two decades, with declining numbers of rural lawyers compounding access issues for communities already struggling with geographic isolation. This growing crisis threatens foundational principles of our justice system and requires thoughtful policy solutions that address both immediate needs and long-term sustainability.

The Geography of Justice Disparity

Rural America’s attorney shortage has reached critical levels in many states. Counties with populations under 15,000 frequently have fewer than ten practicing attorneys, with some having none at all. South Dakota exemplifies this problem, where in 2013, over 65% of its attorneys practiced in just four urban counties, leaving the remaining 62 counties to share the rest. Similarly, Georgia has six counties without a single resident attorney, while Nebraska reports that 12 of its 93 counties lack even one lawyer. This scarcity creates what researchers call “attorney deserts”—regions where residents must travel prohibitive distances to access legal representation. The impact falls disproportionately on elderly, low-income, and disabled populations who face additional transportation challenges. Unlike urban areas where legal aid organizations and pro bono services help fill gaps, rural communities often lack these institutional safety nets entirely.

Historical Context and Contributing Factors

The rural attorney shortage stems from multiple converging trends. Historically, small-town lawyers functioned as community pillars, handling everything from wills to criminal defense. However, the legal profession has undergone dramatic transformation since the mid-20th century. Law school curricula increasingly focus on specialized corporate practice rather than general practice skills needed in rural settings. Meanwhile, educational debt has skyrocketed, making lower-paying rural practice financially untenable for many graduates. Demographic shifts have further exacerbated the problem, with rural population decline creating a perceived lack of professional opportunities. The “graying” of the rural bar presents another challenge—many practicing rural attorneys approach retirement age without successors willing to take over their practices. This creates a troubling scenario where decades of local legal knowledge and client relationships disappear when these attorneys retire, leaving communities without institutional memory or established legal resources.

Consequences for Rural Communities

The attorney shortage creates cascading effects throughout rural justice systems. Without adequate attorney numbers, court proceedings face delays, increasing backlogs and postponing resolution of important matters. Family law cases involving custody, divorce, and child support—already emotionally charged—stretch for months longer than necessary. In criminal matters, public defender shortages mean defendants may wait in jail for extended periods before receiving representation, raising serious constitutional concerns. Local governments struggle to find qualified counsel for essential functions like drafting ordinances or handling municipal litigation. Economic development suffers too, as businesses hesitate to locate in communities lacking legal infrastructure necessary for commercial operations. Perhaps most concerning, the absence of attorneys often means rural residents simply forego legal help altogether. Unresolved legal problems frequently cascade into larger issues—unaddressed domestic violence, unchallenged evictions, or missed opportunities for disability benefits—creating unnecessary suffering and community instability.

Innovative Solutions and Promising Programs

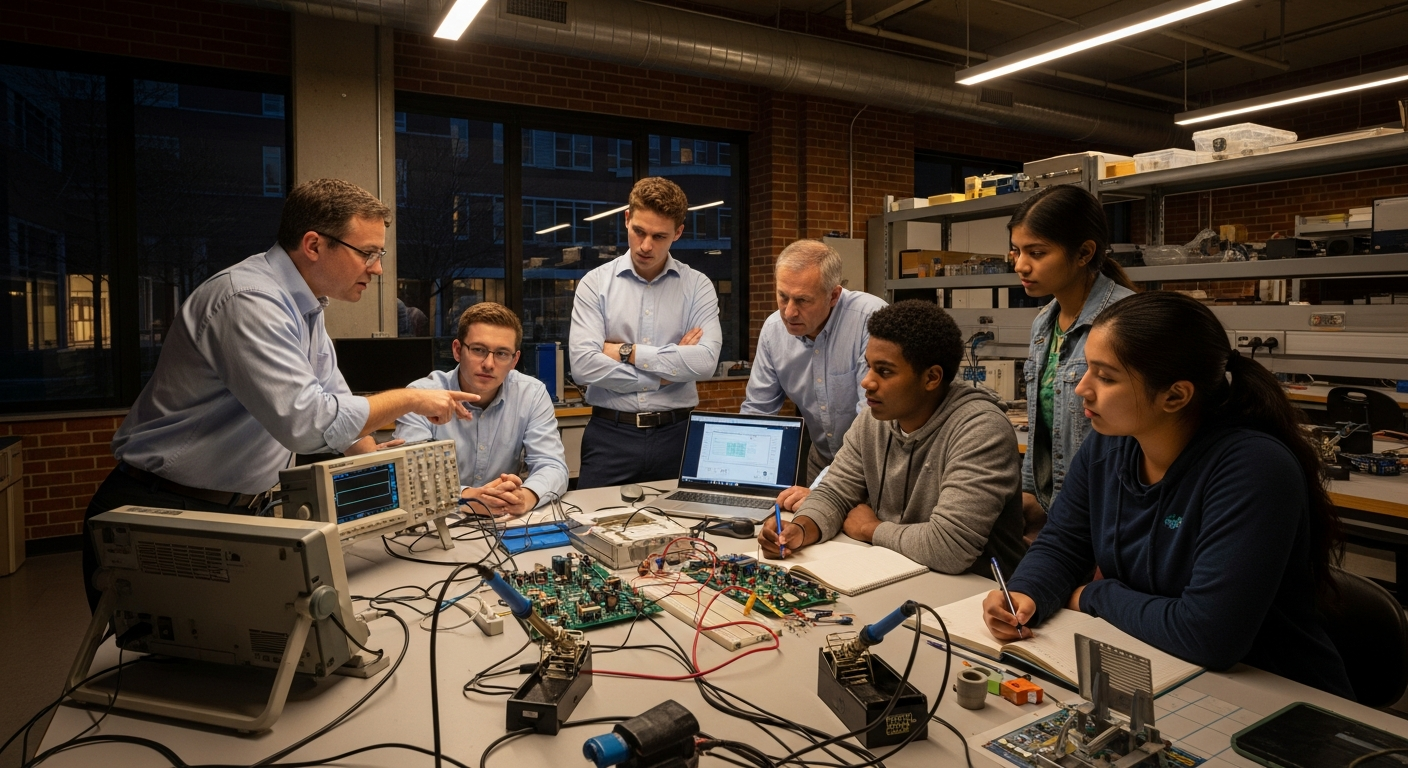

Several states have developed innovative responses to the rural justice gap. South Dakota’s Rural Attorney Recruitment Program offers participants annual subsidies of approximately $12,000 for five years if they commit to practicing in counties with populations under 10,000. Since implementation in 2013, the program has placed over two dozen attorneys in underserved communities. Maine has pioneered a similar approach with its Rural Practice Fellowship, providing stipends to law students who complete summer internships in rural counties. Nebraska’s Rural Practice Initiative combines loan forgiveness with mentorship opportunities, pairing new attorneys with established practitioners nearing retirement. Technology offers another promising avenue, with virtual legal clinics expanding reach into remote areas. The Legal Services Corporation has funded several such initiatives, including Montana Legal Services Association’s videoconferencing system connecting rural clients with urban attorneys. Law schools are also adapting curriculum to better prepare graduates for rural practice, with institutions like University of Arkansas developing specialized tracks emphasizing the unique challenges and rewards of small-town legal work.

Policy Recommendations and Future Directions

Addressing the rural attorney shortage requires comprehensive policy approaches at multiple levels. Federal student loan reform should expand forgiveness programs specifically targeting rural legal practice, similar to existing programs for rural healthcare providers. States should implement tax incentives for attorneys establishing rural practices, offsetting initial income disparities compared to urban settings. Bar associations must actively promote rural practice through dedicated committees, mentorship programs, and continuing education tailored to general practitioners’ needs. Technology infrastructure investments are equally critical—expanding broadband access enables remote court appearances and virtual consultations, reducing travel burdens. Law schools should develop admissions policies favoring students from rural backgrounds, who research shows are more likely to return to similar communities. Finally, community engagement proves essential—local governments might offer office space subsidies or housing assistance to attract attorneys, while community foundations could establish “lawyer incubators” providing shared administrative support during practice establishment. These layered approaches acknowledge that no single solution will reverse decades of professional migration away from rural America.

The Path Forward

The rural attorney shortage represents more than a professional distribution problem—it constitutes a fundamental access to justice crisis threatening constitutional guarantees. As legal resources increasingly concentrate in metropolitan areas, rural Americans face growing barriers to resolving disputes, protecting rights, and participating fully in the justice system. Promising initiatives provide hope, demonstrating that targeted programs can successfully attract attorneys to underserved communities. However, sustainable solutions require ongoing commitment from government entities, educational institutions, professional associations, and communities themselves. The stakes extend beyond individual cases to the very legitimacy of our legal system, which cannot claim equal justice while allowing geography to determine access to representation. By approaching this challenge with creativity and determination, stakeholders can ensure that rural Americans receive the legal services necessary for vibrant, functioning communities—fulfilling the promise of justice for all, regardless of zip code.